Claims on food labels in Australia: health, nutrition content and other marketing claims

Australia and New Zealand’s Food Standards Code sets out requirements for manufacturers wanting to make nutrition content claims (e.g. ‘low in fat’) and health claims (e.g. ‘nuts contribute to heart health’) on food labels. Consumer protection laws in Australia also require that food labels do not misinform consumers through false, misleading or deceptive representations.

Key Evidence

There is evidence that the presence of claims likely leads consumers to perceive labelled foods to be healthier when compared with foods without a claim. When claims are made on unhealthy products, they can create a ‘health halo’, potentially misleading consumers to perceive the products as healthier than they are.

The Food Standards Code sets out rules for when some claims can be made, however, many claims on food labels are not covered by specific regulation under the Code.

State and territory governments in Australia are responsible for monitoring compliance with the Food Standards Code, including regulations related to claims.

Public health organisations call for changes to the regulation, monitoring and enforcement of claims to better safeguard public health.

Types of claims

In Australia, there are two types of voluntary claims that are expressly permitted or regulated under the Food Standards Code (the Code): nutrition content claims and health claims, both regulated by Standard 1.2.7 of the Code. Marketing claims are also commonly made in addition to these.

Nutrition content claims are claims about the content of certain nutrients or substances in a food. They fall into two categories:

- nutrition content claims that can only be used when certain criteria set out in the Code apply (such as ‘no added sugar’, ‘low in fat’ or ‘good source of calcium’). For example, a product labelled a ‘good source of calcium’ must contain a minimum amount of calcium specified in the Code;12 and

- nutrition content claims that simply describe the presence or absence of certain nutrients or substances (such as ‘free from preservatives’ or ‘contains wholegrains’).

Health claims suggest a relationship between a food and a particular health benefit that is supported by scientific evidence. Health claims are only permitted on foods that meet the Nutrient Profiling Scoring Criterion which excludes foods higher in saturated fat, sugar and/or salt. Where foods meet this criterion, the Code outlines stringent requirements for when health claims can be made on that food.

Health claims fall into two categories: general level and high level claims.

General level health claims link the food, or a nutrient or substance in the food, with an effect on health. For example, ‘protein helps increase feelings of fullness’ or ‘nuts contribute to heart health’.3 Food manufacturers can base their claims on more than 200 pre-approved general-level health claims, which can be found here. Alternatively, food manufacturers can establish a new general-level health claim by following detailed requirements set out in the Code, including conducting a systematic review and notifying Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ).4

High level health claims link a nutrient or substance in the food to a disease or a biomarker of a disease. For example, ‘Diets high in calcium may reduce the risk of osteoporosis in people 65 years and over’ or ‘Phytosterols may reduce blood cholesterol’.1 There are 13 pre-approved high-level health claims set out in the Code, subject to restrictions to prevent misleading usage. For example, the claim that a ‘diet containing a high amount of both fruit and vegetables reduces the risk of coronary heart disease’ cannot be applied to fruit or vegetable juices, and is limited to foods that contain at least 90% fruit or vegetable by weight.5 FSANZ has a High Level Health Claims Committee that considers applications for health claims.6

Marketing claims

Increasingly, food manufacturers are making use of claims that are not specifically permitted or regulated under the Food Standards Code. These claims are very common and are made about non-nutrient characteristics of the food.7 They range from descriptive words such as the terms “wholesome” and “natural” that are not objectively verified or defined, to broader descriptions such as ‘great for tiny hands’ or ‘no nasties’.

Impact of claims

Claims are ostensibly used to provide information to consumers, but they typically serve as marketing tactics.

Evidence suggests that claims can shape perceptions of a product’s healthiness and influence purchasing decisions, regardless of the actual nutritional quality of the products.8 This means that claims can make a product appear healthier or lower in energy (kilojoules/calories) than it really is.910 In these cases, claims are said to have a ‘health halo’ effect, potentially misleading consumers.11

For example, claims that have a ‘health halo’ effect can reduce the likelihood of a consumer looking at the comprehensive nutrition information provided on the pack.12 Claims emphasising positive attributes, such as ‘low-fat’, may lead to higher consumption due to the perception that the product is inherently healthy.9 Even when claims are accompanied by other types of labelling, for example summary nutrition information, such as the Health Star Rating (HSR) and nutrition warning labels, the effects of claims can still persist. Research supports these concerns:

- For instance, a study investigating different forms of labelling found that both nutrition content claims and product titles (e.g., ‘protein bar’) increased perceptions of protein content in the product. Even when other types of labelling were present on these products, such as a warning label indicating high sugar content, consumers still perceived the product as healthy based on the product title.11

- A study from Chile, where warning labels are required for products high in sugar, fat, sodium, and/or energy content, showed that nutrition content claims like ‘high in fibre’ or ‘low fat’ on breakfast cereals still enhanced perceptions of healthfulness. While warning labels reduced these perceptions, they didn’t fully negate the influence of nutrient claims.13

There is mixed evidence of the impact of having both claims and nutrition declarations (e.g., the nutrition information panel) on food packaging. Some studies have shown that the presence of nutrition declarations can mitigate the impact of claims on consumer perceptions of product healthiness.8 Other studies have shown that the presence of claims on front-of-pack leads to less use of nutrition declarations on back-of-pack.8

The impact of claims on consumer behaviour and perceptions can vary depending on the type of claim, the product, and consumer characteristics.1014 In an Australian study, participants reported being sceptical of claims and suspicious of food manufacturers and the food industry.10 However, participants still used claims to guide purchasing decisions, particularly for foods that were difficult to assess how healthy they were, such as muesli bars.10 There is evidence that consumers may be willing to pay more for products with health or nutrition claims, particularly when these claims are linked to proven health benefits.8

Proposed changes to regulation of claims

Public health organisations have recommended increased regulation of claims in Australia and New Zealand, including restrictions on the use of nutrition content claims on products that are not considered ‘healthy’ overall.12 While no country has yet implemented restrictions on nutrition content claims based on the overall healthfulness of the food,15 restrictions on claims could be applied across the food supply, or targeted at particular products or population groups. For example, the World Health Organization recommends that no claims are permitted on commercial foods for infants and young children, recognising the particular vulnerability of this population group.16

Compliance with and enforcement of regulations

Ensuring food industry compliance with the Code, including health and nutrition content claims, is principally the responsibility of state and territory governments in Australia.17 Current enforcement efforts are largely ‘passive’, with limited surveillance and a reliance on complaints from interested organisations and consumers to identify breaches.18 The Public Health Association of Australia has argued that surveillance of food labels regarding compliance with the Code should be enhanced considerably, stressing the need for dedicated enforcement mechanisms to safeguard public health.19

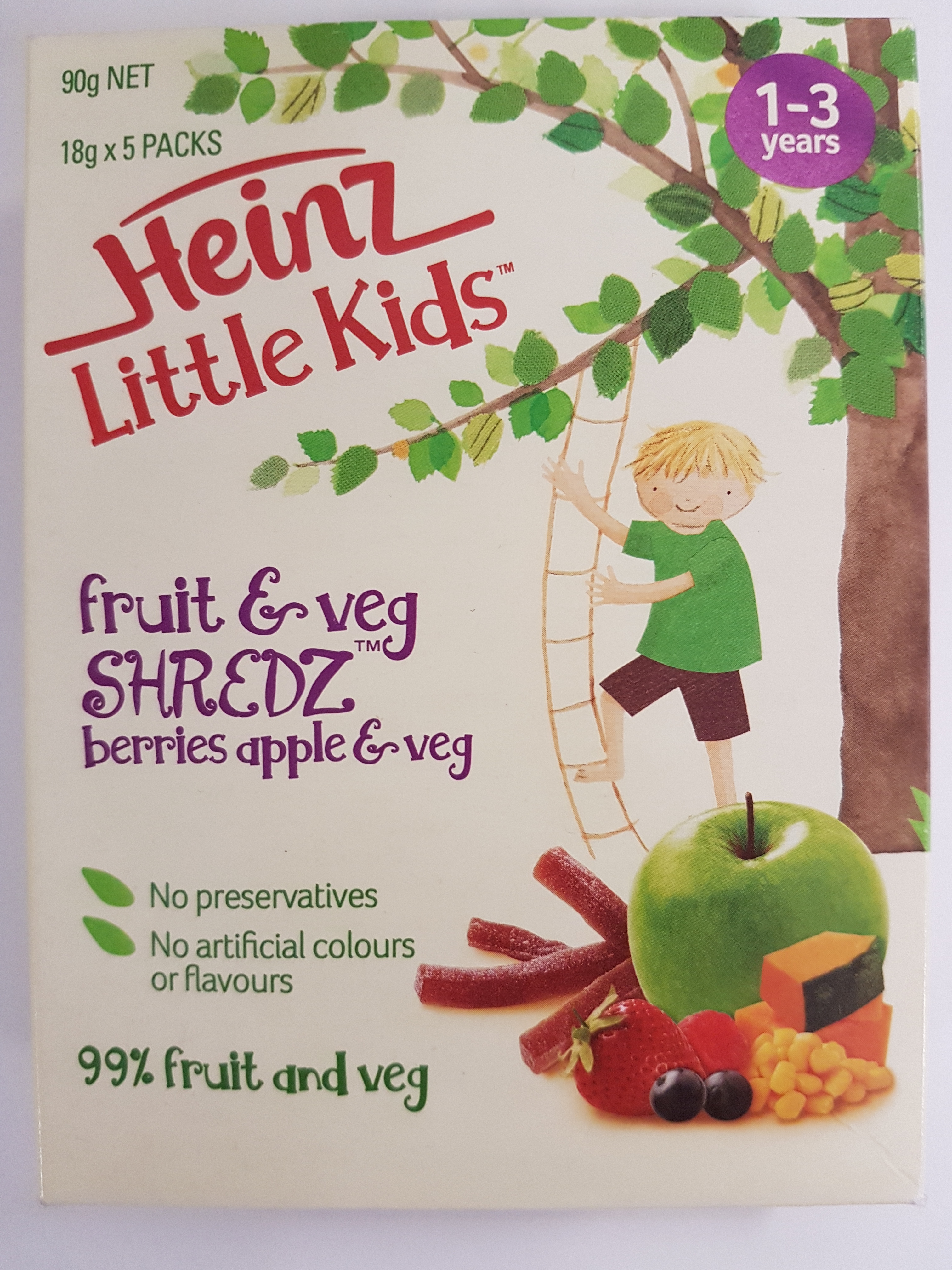

In addition to complying with the Code, consumer protection laws in Australia also apply to claims and other forms of food marketing, including prohibitions on making false or misleading or deceptive representations, with the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) responsible for enforcement at a national level. A notable example in 2018, involved ACCC’s case against H.J Heinz Company Australia Ltd (Heinz) for a claim that its Little Kids Shredz as a nutritious toddler snack.19 The ACCC action followed a complaint by the Obesity Policy Coalition (now Food for Health Alliance) about the products, which had pictures of fruit and vegetables on the packaging together with statements such as ‘99% fruit and veg’ - when in fact the product was predominantly made from fruit juice, fruit concentrate, fruit paste or fruit puree and therefore contained more than 60% sugar and were high in energy and low in fibre. In 2018, the Federal Court ruled against Heinz, finding its claim that the product was beneficial to the health of toddlers misleading. The Federal Court emphasized the potential harm of excessive sugar on children’s dental health and overall well-being, ultimately imposing a $2.25 million penalty.2021

Despite the occurrence of this case, claims continue to be heavily used on infant and toddler foods that do not meet health standards. A recent study found that 72% of Australian commercial foods for young children aged less than 36 months failed to meet all WHO nutrition recommendations, yet all surveyed products featured claims, with an average of eight per product, and some displaying up to 20 claims.22

To improve label comprehension and prevent misinterpretation, public health recommend that governments apply disqualifying conditions for the use of claims on foods based on overall nutritional quality,8 and for commercial infant and toddler foods, prohibit all claims.1623

Source: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission

Content for this page was updated and reviewed by Neha Lalchandani, Josephine Marshall and Gary Sacks at GLOBE, Institute for Health Transformation, Deakin University. For more information about the approach to content on the site please see About | Obesity Evidence Hub.