Promotional channels and techniques: unhealthy food

Children are exposed to unhealthy food marketing over the course of their day through various channels. This includes paid advertising, product placement and branding, sponsorship, product design and packaging. Digital media has created new marketing opportunities, for example food-themed game applications (‘apps’), and provides data that brands can use to target children based on their online habits.

Key Evidence

Traditional and emerging techniques and channels are used to market unhealthy food to children

Internet data can be used to build detailed profiles of individuals for marketing purposes

Portraying unhealthy food as fun is a strategy commonly used to appeal to children

Children are exposed to unhealthy food marketing throughout their day – at school, in shops, outdoors, when they play and watch sport, watch television or use social media. With children’s digital media consumption growing rapidly, the internet has become a major platform for food marketing.1 Novel, immersive techniques such as food-themed game applications (‘apps’) deliver marketing to children anytime, anywhere on portable devices such as smartphones.

Unhealthy food marketing to children includes traditional purchased advertising as well as ‘native advertising’ which mimics the look and type of content on a particular platform and therefore may not be recognised as advertising. Social media marketing is embedded into engaging media content which children are encouraged to share with peers, and online ‘influencers’ are used to promote unhealthy food brands on platforms such as Instagram.1

Digital media give marketers data that can be used to target children based on their online habits. Online tracking methods are used widely including geo-tracking on smartphones, and marketers are building extensive, detailed profiles of anyone using the internet in order to tailor their marketing messages in unprecedented ways.

The World Health Organization’s Regional Office for Europe explains:

Advertising delivered to users on the Internet is tailored either to the content that a user is viewing on a site (contextual advertising) or to characteristics and preferences of each individual user (online behavioural advertising). To deliver contextual advertising, information on users is collected within the website, app or platform itself. To deliver online behavioural advertising, all participants in the advertising ecosystem collect and sell extensive information on users, drawn from dozens or more trackers on any one site or platform. Information on users is merged from multiple Internet locations and devices to create deep individual profiles that go far beyond basic demographics. User profiles include detailed data on online browsing activity, devices and networks used, geo-locations, personal preferences and “likes” and social activities in digital social networks.2

By drawing on extremely fine-grained analyses of children’s behaviour, advertisers seek to locate and identify those who are most susceptible to their messages.2 They follow children “throughout the day, at moments of happiness, frustration, hunger and intent” to deliver advertising with maximum impact. Marketers aim to engage children in emotional, entertaining experiences and encourage them to share these with friends.

While US legislation has attempted to restrict online tracking of children, its effectiveness is debatable. The US Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) is applied by many countries internationally and stipulates that personally identifiable information may not be collected from children under 13 years without parental consent.3 The legislation has reportedly stopped “some egregious predatory data practices”, however it has substantial gaps and does not apply to children older than 13 years. Many sites and apps do not comply with COPPA, children may lie about their age and parents may consent to their children’s data being collected without understanding the implications.3

Channels and techniques used to market unhealthy food to children

Advertising

- Broadcast: including TV and radio

- Print media: including newspapers, magazines and comic books

- Online: including on social media and video platforms such as YouTube

- Outdoors: including billboards, posters and public transport

- Cinemas

Product placement and branding

- Product placement e.g. in TV, radio, films, computer games

- Branded books e.g. counting books for pre-schoolers

- Branded toys e.g. Coles Little Shop promotion

- Branded computer games and apps

- Branded and/or interactive web sites (with puzzles and games) e.g. McDonald’s Happy Meal website

Source: AdNews

Sponsorship

- TV and radio programs

- Events: including community and school events

- Educational materials and equipment

- School breakfast or lunch programmes

- Venues

- Sports teams (amateur and professional)

Source: McDonald’s Australia

Direct marketing

- Text messaging to mobile phones

- Contests, prizes

- Vouchers used as educational or sporting awards

- Promotion and sampling schemes in schools e.g. chocolate drives

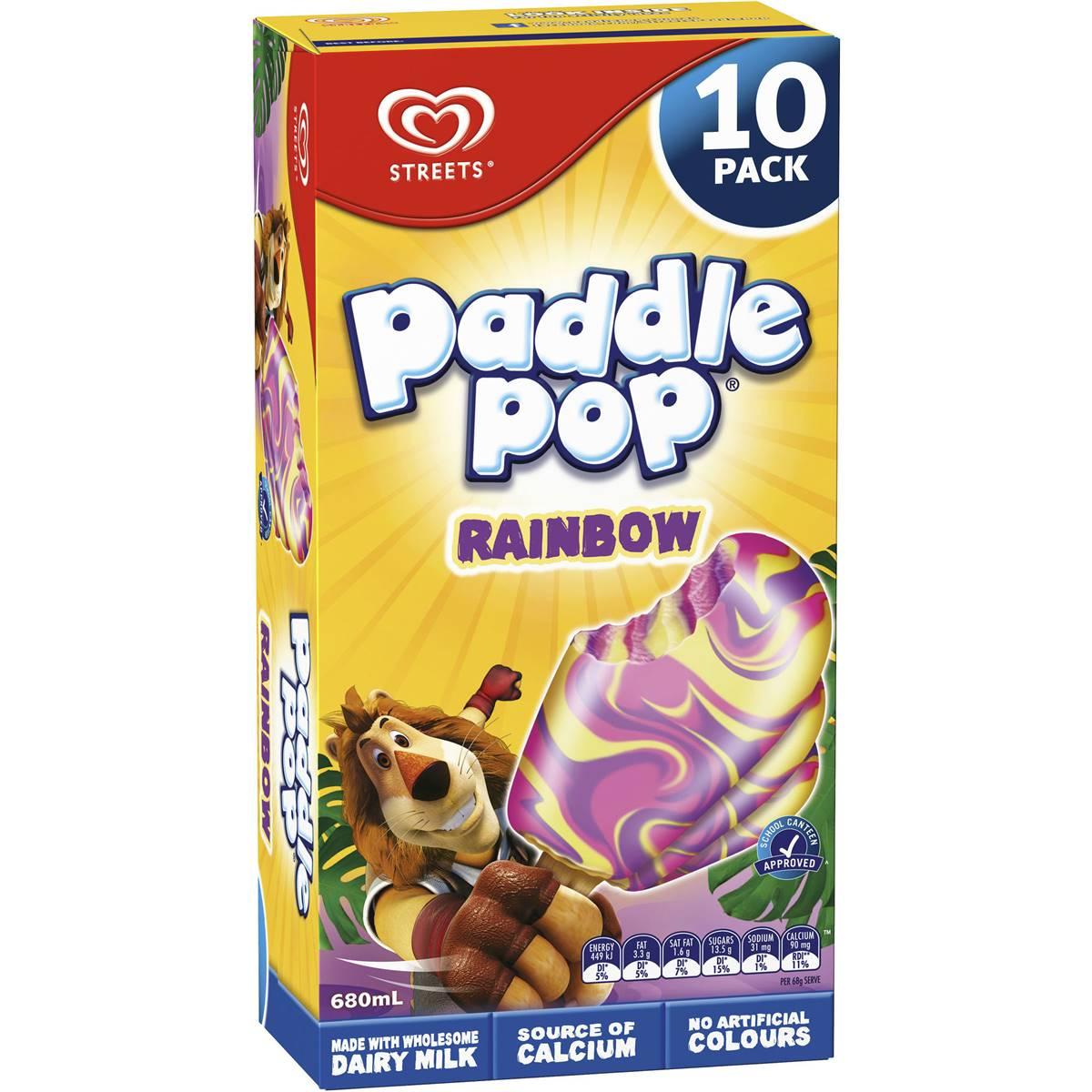

Product design and packaging

- Product design: colours and shapes e.g. dinosaur-shaped products

- Packaging design: imagery, colours

- Product portions e.g. king size, duo packs

- In-pack and on-pack promotions e.g. gifts, puzzles, vouchers

Source: Woolworths

Point-of-sale

- On-shelf displays

- Displays at check-outs and end-of-aisles in supermarkets

- Vending machines in schools and youth clubs

- Loyalty schemes

- Free samples and tastings

'Fun' in unhealthy food marketing

Portraying unhealthy food as ‘fun’ or linking it to fun activities is a strategy commonly used to appeal to children.4 To harness the important role of packaging in appealing to young children,5 brands often include references to ‘fun’ or ‘play’ or use cartoon characters on the pack. They use fun-sounding names (e.g. party mix lollies, fun-sized chocolate bars), fun shapes (e.g. Freddo Frog), and fun colours.6 McDonald’s was an early adopter of this technique in 1979 when it launched its Happy Meal, a children’s meal and toy in a colourful box which remains popular around the world today.7 PepsiCo characterises part of its product range as the ‘Fun-for-You’ portfolio, which includes the soft drink brand Pepsi and chips Doritos and Cheetos. (There is also a ‘Better-for-You’ portfolio and a ‘Good-for-You’ portfolio.)7

A focus on ‘fun’ in unhealthy food marketing to children can reconfigure relationships with food, distract from health concerns and increase consumption.7 Fun has positive connotations and attempts to deny fun are met with resistance (such as ‘nanny state’ criticisms). Children may seek to eat or snack as a source of entertainment rather than because they are hungry, or eat more than necessary because the food is ‘fun’. For older children, the focus shifts to ‘cool’ and messages are often spread through viral marketing which encourages children to share content with their peers.8 An Australian study cited the example of Coca-Cola’s Talking Penguin mobile phone application in which users directed a penguin to perform various actions such as kicking a soccer ball or dancing, and could upload the resulting video to Facebook.8